Mechanical ventilators are making headlines these days because of the Coronavirus-19, widely regarded as a flu but which is actually a respiratory disease that attacks the lungs. The key to minimizing the death toll for those with virulent infections is the availability of mechanical ventilators that help people breathe when their own lungs can’t.

Reports of potential ventilator shortages have resulted in the floating of ideas about car makers converting vehicle manufacturing lines into assembly lines for ventilators. Even Elon Musk has gotten into the act saying in a tweet that Tesla and SpaceX will make ventilators if there is a shortage. There is also a movement underway to create an open-source mechanical ventilator design. No word yet on how such a contraption would get through regulatory requirements.

Of course, engineers realize that an assembly line for a car probably has little in common with an assembly line for a ventilator. And patients put on a ventilator produced by a carmaker, or one made cobbled together by backyard mechanics from an open-source design, might well wonder whether the ventilator would kill them before the virus did.

Nevertheless, Elon Musk is correct in tweeting out that ventilators “are not difficult.” Here are the principles behind a ventilator and its main components.

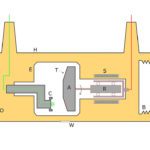

Most commercial ventilators today use an operating principle called intermittent positive pressure ventilation. Here a positive airway opening pressure is applied intermittently. The positive pressure pushes air from a tank (actually air plus oxygen) into the lungs.

The basic equipment necessary to implement this kind of ventilator includes tanks of compressed air and oxygen, connecting tubes, two valves called inspiratory and expiratory valves, a Y connection for the connecting tubes, a ventilator mask that goes on the patient, and sensors that monitor the air pressures and volumes through the breathing cycle. The breathing cycle begins with the inspiratory valve open to allow airflow to the patient. The ventilator senses when pressure reaches a preset limit, meaning the lungs are full. At this point, the inspiratory valve shuts off the air supply and the expiratory valve opens, allowing the lungs to expel their air. The system eventually senses that air pressure has dropped to a preset level, signaling that the lungs have expelled all their air. At this point the expiratory valve shuts, the inspiratory valve opens, and the cycle repeats.

The basic equipment necessary to implement this kind of ventilator includes tanks of compressed air and oxygen, connecting tubes, two valves called inspiratory and expiratory valves, a Y connection for the connecting tubes, a ventilator mask that goes on the patient, and sensors that monitor the air pressures and volumes through the breathing cycle. The breathing cycle begins with the inspiratory valve open to allow airflow to the patient. The ventilator senses when pressure reaches a preset limit, meaning the lungs are full. At this point, the inspiratory valve shuts off the air supply and the expiratory valve opens, allowing the lungs to expel their air. The system eventually senses that air pressure has dropped to a preset level, signaling that the lungs have expelled all their air. At this point the expiratory valve shuts, the inspiratory valve opens, and the cycle repeats.

The fact that ventilators use pressure as the primary mechanism for controlling airflow has allowed hospitals to get creative when there is a shortage of ventilators. For example, it’s possible to splice multiple patients into a single ventilator by simply adding T connections to the air supply tubing. The proviso is that patients added in parallel this way all must have about the same lung capacity.

Rather than convert automotive assembly lines to handle ventilators, a better approach might be to help existing suppliers ramp up. One of the more promising developments in this regard comes from a company called OneBreath, formed by Stanford University researchers. The OneBreath ventilator isn’t yet available but is designed to be an inexpensive device for third-world countries. In interviews, the founders say they’d need both money and fast-track regulatory approval to get their inexpensive ventilators on the market asap.

Much appreciated and timely. THANKS LEE!

As a manufacturing engineering with close to 40 years experience I can tell you there are a lot of sub-assembly lines feeding components that would be readily adaptable. The main assembly lines are too big. Dashboards, car seats both have a lot of sub-assemblies that are about the same size and complexity as a ventilator.

The writer appears to conflate auto manufacturing narrowly with car assembly plants.

Many years ago General Motors built a vast factory in Kokomo Indiana largely dedicated to the development and manufacture of electronic automotive components. And automotive electronics have evolved into rather sophisticated systems and devices of many types. The Kokomo plant is presently manufacturing ventilators jointly with an existing ventilator manufacturer under contract for the U.S, government. I expect this can be done at the Kokomo GM plant as capably as anywhere. And it’s a practical match too, the way auto sales have been reduced by the pandemic.