If you disassemble an electrolytic capacitor and a supercapacitor, you might have trouble distinguishing differences between the two unless you had a practiced eye. Physically, the two can resemble each other though their electrical performance differs drastically.

First a few basics. Ordinary capacitors, of course, are characterized by metal plates separated by a dielectric. In supercapacitors, the capacitance mechanism is electrochemical, consisting of electrostatic double-layer capacitance and electrochemical pseudo-capacitance. These new functions enhance the combined capacitance, permitting greater efficiency and size reduction.

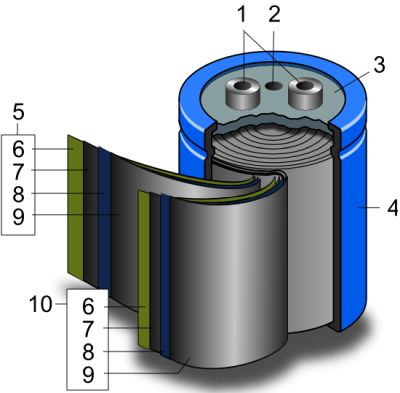

The interesting thing about supercapacitors is that their physical structure looks like an ordinary capacitor–Two leaves with a separator material between them, rolled up in a cylindrical housing. That’s because though supercapacitors have six components, three of them consist of coatings.

The first layer of a supercapacitor is an electrode, though in supercapacitor parlance it is called a current collector. It is basically a low-resistance material such as metal foil. Most commercial supercapacitors use graphite foil, but type of foil used depends on the electrolyte. In YouTube videos that show do-it-yourself supercapacitors, you’ll see current collectors made from aluminum foil, nickel foil, lead foil, copper foil, zinc or magnesium foil, as well as others.

Next is an active material, usually carbon because it has a large active area. A common choice for home-brew supercaps is activated carbon as used for cleaning fish tanks. This has to be put into the form of a paste that can be spread on the current collector. The usual technique is to put the activated carbon in a blender until it is a fine dust, then add a carrier, often acetone because the binder in the carbon dissolves in acetone. Then you coat the foil with the active carbon paste and dry it out on a hot plate.

Next comes a separator layer. Home-brew supercaps may use tissue paper, ordinary paper towels, ordinary toilet paper–basically, just a thin sheet of paper.

On the other current collector goes another layer of carbon material if the supercap is of the symmetric variety. In a symmetric supercapacitor, both current collectors are the same material. Asymmetric supercapacitors use two different materials for electrodes. In the latter case, common choices in home-brew supercaps for the second current collector material include manganese dioxide and vanadium pentoxide–basically oxides of transition metals. (Transition metals are those having valence electrons in two shells instead of only one.)

Finally, supercaps contain an electrolyte. The simplest DIY supercaps described on YouTube use table salt dissolved in water but neutral electrolytes can include sodium sulfate, acidic electrolytes may use surfuric acid, and alkali electrolytes may use lithium hydroxide.

You can find supercaps on YouTube thus described producing capacitance values of 4 F at 1.2 V for a single-layer device measuring 1 cm2.

The activated carbon allows supercapacitors to store electrical energy either electrostatically or electrochemically where ordinary capacitors only store energy electrostatically. But you do find ordinary capacitors that, like supercapacitors, depend on a coating of one of their electrodes for their operation. That kind of capacitor is an electrolytic capacitor. Once again, you can find YouTube videos for DIY electrolytic capacitors that shed light on the their construction.

The usual approach to a DIY electrolytic capacitor is to start with pieces of an aluminum soda. One serves as the positive capacitor plate, the other as the connection to the electrolyte. The aluminum serving as the positive electrode gets an aluminum oxide coating which serves as the insulator between the two capacitor plates. The electrolyte serves as the other capacitor plate. The point of the other aluminum electrode is to make a wide-area contact with the electrolyte serving as the negative electrode.

The usual way of creating the oxide coating on the positive electrode is to first immerse the two soda-can electrodes in an electrolyte (usually baking soda dissolved in distilled water to saturation) and then applying a dc voltage (called a forming voltage) while monitoring the current flow. The dropping of the current to a miniscule amount signals that the oxide layer has formed.

Use of an oxide for the dielectric minimizes the distance between the two capacitor plates and, in so doing, reduce the required volume needed to produce a given capacitance. As with supercapacitors, commercial electrolytic capacitors also typically contain a separator material (often thin tissue) between the two metal electrodes. But the separator doesn’t function as the dielectric; it is there to hold the electrolyte. Exploded view diagrams of electrolyte capacitors don’t often make this distinction, so it can be a point of confusion among technical personnel trying to figure out why electrolytic caps look so much like ordinary caps.

There are also hybrid capacitors, including the lithium-ion capacitor, which use electrodes having contrasting characteristics, either electrostatic capacitance or chemical capacitance. Supercapacitors are polarized by design with asymmetric electrodes or by a potential applied during manufacturing.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.