The cost of an oscilloscope depends primarily on its bandwidth and, to a lesser degree, on added features such as an internal arbitrary function generator (AFG) and other options. If the price of the instrument is acceptable, the rational choice would be to go for the best device immediately. But in the real world most of us have multiple priorities and even large, bountifully funded institutions like to spend money wisely. A good plan is to carefully examine today’s bandwidth requirements with an eye on the future.

The major players – Tektronix Inc., Teledyne LeCroy, and Keysight Technologies (formerly Agilent) – offer models that are bandwidth-upgradable. So it may be feasible to economize on bandwidth initially and get other features.

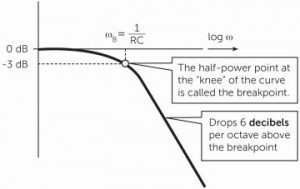

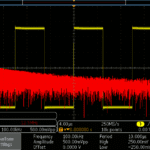

The underlying fact is that signal amplitude generally declines as frequency rises. This is a consequence of parasitic capacitive reactance which appears in parallel with the source and load. Capacitive reactance falls as frequency rises, so it increasingly shunts out higher frequency signals. Simultaneously, parasitic inductive reactance, appearing in series with the source and load, rises with frequency to further degrade signal amplitude.

This attenuation applies along the entire length of the signal path, from the tip of the probe to the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) and beyond. Oscilloscope designers go to great lengths to reduce parasitic inductance and capacitance along the signal path. Their efforts have brought enormous gains in frequency response. But these advances are costly to implement and this fact is reflected in the price of the equipment. So instrument buyers must take a hard look at present and future bandwidth requirements.

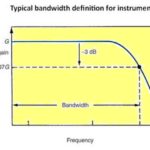

The traditional concept was that instrument bandwidth should be five times the signal to be observed. That was good enough in strictly analog environments, but today’s increasingly digital circumstances demand a lot of fine tuning. A 100-MHz sine wave that has a 1-V peak-to-peak amplitude will look like a good sine wave. But if you estimate the amplitude by looking at the graticule or by using the built-in voltmeter, the apparent amplitude could be around 700 mV peak-to-peak, in accordance with the 3-dB roll-off point that determines rated bandwidth.

This same 100-MHz sine wave with the 1-V peak-to-peak amplitude will display accurately with a 300 MHz instrument. But if it is a square wave with a fast rise time that is being observed, it could appear like a sine wave, albeit with the correct frequency displayed, unless it is viewed with an instrument having a bandwidth on the order of 500 MHz.

Oscilloscopes rated above 1 GHz typically have a flat frequency response almost to their rated bandwidth, whereupon response falls off abruptly. If the scope is rated under 1 GHz, the frequency response will begin to fall off earlier but will show less attenuation below -3 dB, which is, by definition, where the two curves intersect.

A critical component in bandwidth selection is the required accuracy, which depends upon the application and must be decided by the user in advance of any calculations.

The maximum frequency component of the signal being tested is known as the knee frequency. If the required accuracy is 20%, the bandwidth requirement is equal to the knee frequency. If the required accuracy is 10% and the frequency response conforms to the Gaussian curve, the bandwidth requirement is 1.3 times the knee frequency. If the frequency response conforms to the maximally flat curve, the required bandwidth is 1.2 times the knee frequency.

If the required accuracy is 3% and the frequency response conforms to the Gaussian curve, the bandwidth requirement is 1.9 times the knee frequency. If the frequency response conforms to the maximally flat curve, the bandwidth requirement is 1.4 times the knee frequency.

These guidelines for where the work is in the digital realm make it is possible to ascertain the necessary scope bandwidth and accordingly choose the correct instrument.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.