Ancient people had a clear understanding of sound – how a vibrating object causes oscillating changes in air pressure, which move the eardrum so as to give rise to human perception of sound.

In regard to light, there was less agreement. The pre-Socratic philosopher Empedocles believed light required a definite amount of time to travel from the sun, while Aristotle and many centuries later, Descartes, held the position that light traveled instantaneously.

Galileo satirized this view, having his character Simplicio state “Everyday experience shows that the propagation of light is instantaneous; for when we see a piece of artillery fired at a great distance, the flash reaches our eyes without lapse; but the sound reaches the ear only after a noticeable interval.” Galileo pointed out that this observation demonstrates only that light travels faster than sound.

Ole Rømer, a Danish astronomer working at the Paris Observatory, figured the speed of light by observing Io, one of Jupiter’s moons. By this time, optical telescopes had advanced enough for astronomers to observe and time Io’s periodic eclipses from earth’s point of view behind Jupiter. This metric changed drastically in the course of a year as the earth revolved about the sun, becoming successively closer to and farther from Jupiter and its moons. The duration of the eclipse did not change, but the time of its occurrence varied, and Rømer concluded this was due to the time that light required to travel twice the radius of Earth’s orbit about the sun. This distance was known in Rømer’s time. Taking it into account, he was able to calculate the speed of light. The figure he came up with was 220,000 km/sec, about 26% lower than the true value.

Refined instrumentation and experimental methods made possible increasingly accurate measurements of the speed of light. By 1975 the figure had been found to be 299,792,458 m/sec, accurate to within four parts per billion. Then, in 1983, scientists redefined the meter in terms of the speed of light to get absolute measurement certainty.

Putting this all in perspective, a photon would require over 30 billion years to cross the known universe.

Following Ole Rømer’s first determination in 1676 of the speed of light, increasingly precise instrumentation and methods permitted greater accuracy. But toward the end of the nineteenth century it became obvious that something was radically wrong.

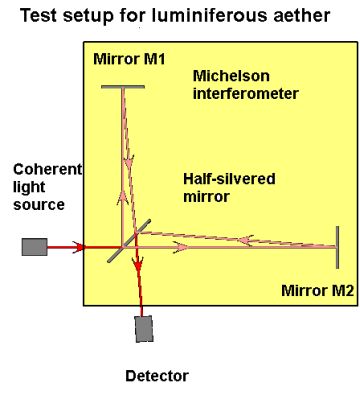

The brilliant theoretician Albert Michelson (1852-1931) and his skilled instrument maker Edward Morley (1838-1923) performed a series of experiments in the 1880s for the purpose of ascertaining the speed of a luminiferous “aether wind” that would reveal the exact speed of the earth’s relative motion through a presumably fixed frame of reference. To everyone’s surprise, it was found that the relative speed of light was the same in both directions regardless of the earth’s motion through space.

The Michelson-Morley experiment was repeated numerous times all with the same null result. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the speed of light was totally problematic. The classical Newtonian certainties concerning time and space were obscured as length contraction was postulated by George FitzGerald and Hendrick Lorentz. This postulation was a straight-forward effort to uphold the idea of a stationary frame of reference defined by a non-moving luminiferous aether.

Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity, laid out in a 1905 paper titled On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies, takes the counter-intuitive position that the speed of light in a vacuum is the same for all observers regardless of their motion or the motion of the light source. This position makes use of the Lorentz-FitzGerald contraction — basically, the idea that there’s a decrease in length of an object as measured by an observer which is traveling at any non-zero velocity relative to the object. But Einstein went well beyond this, asserting that what contracts as a moving body approaches the speed of light is not just the body, but its time-space frame of reference.

According to the Special Theory, the speed of light in a vacuum, denoted c, is a theoretical upper limit on the motion of any physical body, or indeed of information in any form. (Quantum Entanglement would seem to violate this prohibition. It really does not because information is not traveling between the two widely-separated entangled bodies, but just becoming known as a pre-existing condition.)

As a moving body approaches c, both the mass of the body and the energy required to accelerate it will increase. At c, both these variables would become infinite. For this reason, c is a constant that plays a key role in physical reality.

Various warp drive mechanisms have been proposed (such as microwaves oscillating within a cone-shaped container) that would make it possible to exceed c with no input from an outside energy source or fuel. When it comes to a working model, none has been forthcoming.

Recent observation of particles travelling faster than c turned out to be flawed, the amazing data resulting from instrument miscalibration. There have been and will be similar ideas proposed, but as of now c remains indomitable.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.