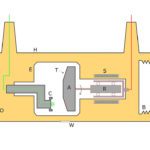

The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) tokamak is an experimental machine designed to harness the energy of fusion. ITER will be the world’s largest tokamak, with a plasma radius of 6.2 m and a plasma volume of 840 m³.

The heart of a tokamak is its doughnut-shaped vacuum chamber. Here, under the influence of extreme heat and pressure, gaseous hydrogen fuel becomes a hot, electrically charged gas called a plasma. The charged particles of the plasma can be shaped and controlled by the massive magnetic coils placed around the vessel; the magnets keep the hot plasma away from the vessel walls.

To start the process, air and impurities are first evacuated from the vacuum chamber. Next, the magnet systems that help to confine and control the plasma turn on and the gaseous fuel is introduced. As a powerful electrical current is run through the vessel, the gas breaks down electrically, becomes ionized (electrons are stripped from the nuclei) and forms the plasma.

More specifically, the most efficient fusion reaction in the laboratory setting is a reaction between two hydrogen isotopes, deuterium and tritium. the fusion between deuterium and tritium nuclei produces one helium nucleus (also called an alpha particle), one neutron, and great amounts of energy. The helium nucleus carries an electric charge which will be subject to the magnetic fields of the tokamak and remain confined within the plasma, contributing to its continued heating. However, approximately 80% of the energy produced is carried away from the plasma by the neutron which has no electrical charge and is therefore unaffected by magnetic fields. The neutrons will be absorbed by the surrounding walls of the tokamak, where their kinetic energy will be transferred to the walls as heat.

First Plasma is scheduled for December 2025. This will be the official start of ITER operation.

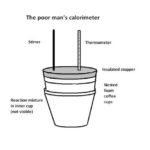

That said, you might wonder how scientists plan to measure something sitting at a 300 million °C temperature. After all, it’s not like they can stick in a few thermocouples.

All these techniques basically make measurements of light or light generated by particles emitted during the fusion process. Here’s a quick run-down on what they really entail.

The Motional Stark Effect is a way of measuring the internal magnetic fields in high-temperature plasma experiments. MSE gives a measure of the pitch angle of the magnetic field in the plasma. Specifically, it measures the polarization state of light emitted from hydrogen fuel as it passes through a magnetized plasma. As the hydrogen moves through the magnetic field, B, at high velocity, v, it experiences in its reference frame an electric field, E = v x B. The hydrogen atoms are excited via collisions with background plasma and emit visible light which is split into nine spectral lines by the electric field in a phenomenon known as the Stark effect. The polarization of the light is aligned with respect to the magnetic field, so a measurement of the polarization orientation can be used to determine the magnetic field direction in the plasma.

CHERS involves measuring the intensity and/or spectral distribution of photons emitted in the charge exchange collision between fast neutral atoms and plasma ions. After the collision, the ion is left in an excited state which then decays to produce observable photons. Some of the photons are in the visible light range, so they are easy to see with ordinary spectrometers. And the emitted photon rate depends only on the neutral hydrogen beam qualities and the ion density.

CHERS can help scientists get a feel for impurity densities and how ions move across magnetic field lines and can help gauge dynamic plasma properties such as ion temperatures and their velocity of rotation. It is also expected to be helpful in measuring the density and nonthermal velocity of alpha particles produced in the fusion plasma.

Beam-emission spectroscopy is a diagnostic technique that infers local fluctuations in the density of the injected neutral hydrogen beam from fluctuations in the light that’s emitted. BES is usually used to gauge turbulence, particularly where the neutral beam starts to ionize.

Finally, lost-alpha scintillators are a way of detecting alpha particles that get away from the containment of the magnetic field and hit the wall of the vessel, potentially causing damage. Ordinary scintillators absorb the energy of incoming particles and scintillate, that is re-emit the absorbed energy in the form of light. Lost-alpha scintillators work this way as well, but they are sensitive to the alpha particles generated during the fusion reaction. It takes a relatively exotic material to scintillate when hit with alpha particles. But the light that such scintillators emit can be measured using relatively ordinary spectrometers.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.